The Hunt for Earthlike Planets

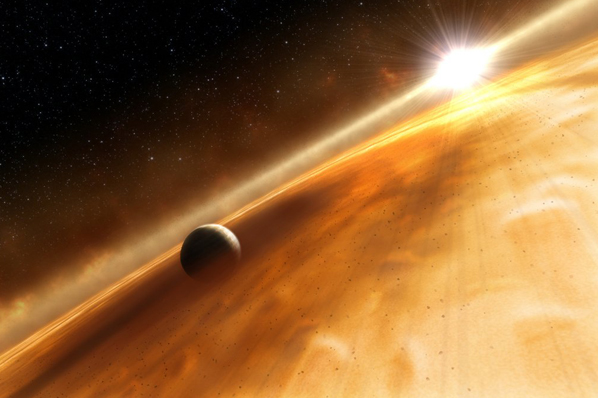

Is there life on other planets? For hundreds, if not thousands, of years, people have been looking at the night sky and wondering who else might be out there. Could there be human-like beings, living on an earth-like planet, orbiting a sun-like star?

So far, science has not delivered many answers about intelligent life in the universe, but researchers did take a bold step forward in 2016 with the discovery of thousands of “exoplanets,” or planets that exist outside our solar system.

In July 2015, the Kepler space telescope captured data about thousands potential planets orbiting stars throughout the universe. Scientists have analyzed that data, and in May 2016, NASA confirmed the existence of 1,284 exoplanets. Nine of these planets are the right size and distance from their stars to have liquid water—a key ingredient for life as we know it.

News reports make the search for exoplanets seem straightforward. You simply point the telescope and analyze the data, right? But how do astronomers know what to look for? After all, it’s not like catching a Pokémon character or reading a label that says “earth-like planet here.”

As veteran planet-hunter Professor Joshua N. Winn explains in The Great Courses’ video The Search for Exoplanets: What Astronomers Know, the hunt for earth-like exoplanets requires sophisticated techniques with names like “astrometry” and “gravitational lensing.” These techniques tell you which stars in the night sky may have a planet orbiting them.

If you were a researcher looking for intelligent life, you would do well to follow the approach NASA uses to find exoplanets:

Start with a very large batch of possible planets. The Kepler telescope casts a wide net and captures data about many possible planets. The bigger the sample of objects that appear to be planets, the greater the chances are of gaining a hit.

Then look for rocky planets the size of earth. Although it is impossible to tell with today’s technology whether these planets are actually solid like earth, scientists make a reasonable guess that objects the size of earth are most likely rocky.

Finally, flag the planets in “habitable zone.” If earth were too close to the sun (like Mercury), it would be too hot to sustain liquid water. If earth were too far from the sun (like Mars), it would be too cold. But there is a “just right” space where liquid water could exist—and that’s where scientists think they’re most likely to find life.

Nine exoplanets have recently joined this select club of earth-like planets orbiting distant stars. Although we can’t know whether they have water, or if that water has allowed for life, humanity is taking big steps in what Professor Winn calls a “momentous scientific journey.”

Join Professor Winn to discover how we find exoplanets, the exploration of super-earths and the elusive earth-like planets, and the search for life on exoplanets in The Search for Exoplanets: What Astronomers Know. Or further your knowledge about astronomy, physics, robotics, and more with the The Great Courses Plus -- get a full month for free when you use this link.

Article sponsored by The Great Courses Plus